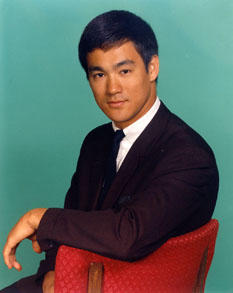

He

is considered by his peers to be the greatest

fighter of the twentieth century, and quite

possibly ever. To the world he was an action

movie star. To his students and disciples he was

a teacher who was gifted with an extraordinary

philosophical mind that he brought to bear, not

only in his martial arts training, but also in

his life and how he lived it. He

is considered by his peers to be the greatest

fighter of the twentieth century, and quite

possibly ever. To the world he was an action

movie star. To his students and disciples he was

a teacher who was gifted with an extraordinary

philosophical mind that he brought to bear, not

only in his martial arts training, but also in

his life and how he lived it.

Bruce Lee was born in San

Francisco in 1940, in the Chinese year of the

dragon. His father was a Chinese actor touring

with the Canton Opera. As a child growing up in

Hong Kong, Bruce was exposed to Tai Chi Chuan by

his father, who practiced it for his health.

Though he learned very little fighting skills

from his father, this was the first exposure

Bruce Lee had to Taoist concepts.

By his teenage years Lee had

begun to get in trouble. The streets of post-war

Hong Kong were rough filled with gangs and

violence. Triads were a constant threat. After

several serious incidents, Lee's parents agreed

to enroll him in gung fu classes.

At the age of thirteen Lee

was accepted into the kwoon (training hall) of

renowned Sifu Yip Man, the head of the Wing Chun

school. Under Yip Man's tutelage, he began to

study the Wing Chun style of fighting as well as

the philosophical underpinnings, which Yip Man

greatly stressed.

Wrote Lee's widow, Linda:

"If there is anything that Yip Man gave to

Bruce which may have crystallized Bruce's

direction in life, it was to interest his student

in the philosophical teachings of Buddha,

Confucius, Lao Tzu, and other great thinkers and

philosophers. As a result, Bruce's mind became

the distillation of the wisdom of such teachers,

specifically, but not exclusively, the deep

teachings of the yin/yang principle."

.

|

At

the age of eighteen, Lee's parents sent him to

America to get him away from the gangs and

violence of Hong Kong. Lee settled in Seattle and

stayed with family friend Ruby Chow, who owned a

restaurant. They often clashed, as Lee refused to

show Chow the elder piety that she felt was due

her under Confucian tradition. While working at

her restaurant he attended Edison technical

School and earned his high school diploma. At

the age of eighteen, Lee's parents sent him to

America to get him away from the gangs and

violence of Hong Kong. Lee settled in Seattle and

stayed with family friend Ruby Chow, who owned a

restaurant. They often clashed, as Lee refused to

show Chow the elder piety that she felt was due

her under Confucian tradition. While working at

her restaurant he attended Edison technical

School and earned his high school diploma.

He quickly developed a

reputation for his gung fu skills and soon had

many people wanting to study under the gifted

nineteen year-old. One of those people, Taky

Kimura, a thirty-eight year-old

Japanese-American, had been in the United States

internment camp during World War II, and suffered

difficulty in getting a decent job afterward,

under the shadow of post-war anti-Japanese

sentiment. Demoralized, Kimura was seeking

something to give him back his self-confidence.

He found that in the young Bruce Lee, who became

his mentor, spiritual guide, and best friend.

Lee went on to the

University of Washington at Seattle where he

majored in philosophy. His grasp of Eastern

concepts was so profound that he became in great

demand as a lecturer on Eastern philosophy.

Lee had avoided setting up a

school of gung fu in Seattle because he wanted to

focus on his education. But, not liking the jobs

he had to do to support himself, he finally

opened one near the university in late 1963. As

he had never achieved instructor rank in Wing

Chun gung fu, he christened his school the Jun

Fan Gung Fu Institute, after his Chinese name.

Bruce Lee was already

beginning to feel discontent with

"styles" of fighting. On the separation

between hard and soft styles of gung fu schools

he said: "It's an illusion. You see, in

reality gentleness/firmness is one inseparable

force of one unceasing interplay of movement. We

hear a lot of teachers claiming their styles are

either soft or hard; these people are clinging

blindly to one partial view of the totality. I

was once asked by a so-called 'kung fu

master'-one of those that really looked the part

with the beard and all-as to what I thought of

Yin and Yang? I simply answered, 'Baloney!' Of

course, he was quite shocked at my answer and

could not come to the realization that 'it' is

never two." Lee understood the false

division that so often traps students of Taoism,

the false division in recognizing Yin and Yang as

opposites, and not as complements.

Lee quit the university and

married Linda Emery. After the wedding, the two

moved to California, where Lee opened another

school. Within a short time Lee had caught the

attention of San Francisco's Chinatown. They were

upset by Lee's practice of teaching the arts to

non-Chinese. For his part, Lee believed that all

humanity was a totality, and did not make the

distinction between races. "Under the sky,

under the heavens, there is but one family."

One day a group of Chinatown

Kung Fu men appeared at Lee's kwoon demanding

that he stop teaching the "gwei-lo" or

foreign devils at once or he would have to fight

their top fighter, Wong Jack Man. Thinking him a

paper tiger, they were startled when he accepted.

When they tried to impose rules and a date for

the fight Lee became angry, saying the fight

would take place immediately and without rules.

His opponent had no choice but to agree.

Lee and Wong Jack Man then

formally bowed and began to fight. Lee fought in

strict Wing Chun style and, combined with Wong

Jack Man's own style, the two seemed to cancel

each other out. After three minutes, Lee finally

managed to put Wong Jack Man on the floor and

forced him to submit.

Though Lee's victory ended

his problems with the Chinatown community, he was

very unhappy with how the fight went. He found

that his style of fighting had held him back; a

fight he should have won easily in a few seconds

took three minutes and a narrow victory. He

realized that he must continue to evolve. The

idea of styles of fighting had come into conflict

with his Taoist beliefs that the way of fighting

is formless and all-encompassing, and that styles

separate the fighter from the truth.

.

|

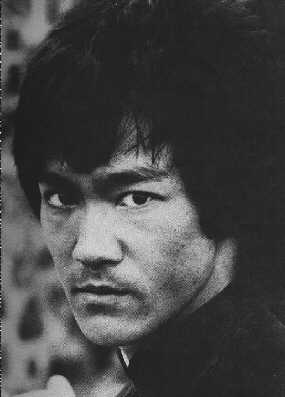

It

was at this point that Bruce's expression of

martial arts and philosophy, Jeet

Kune Do, was born. Its chief

principle of "having no way as way"

borrowed heavily from Lao Tzu, "This is

called shape without shape, form without

object." It

was at this point that Bruce's expression of

martial arts and philosophy, Jeet

Kune Do, was born. Its chief

principle of "having no way as way"

borrowed heavily from Lao Tzu, "This is

called shape without shape, form without

object."

Soon Bruce began to study

other styles; he adopted footwork from fencing

and some hand strikes from western boxing, to

name a few. His philosophy was to "absorb

what is useful, discard what is useless, and add

what is essentially one's own." By November

1966 Bruce had a clear idea of his new vision for

fighting. In 1967 he coined the name Jeet

Kune Do to represent his

personal expression of the martial arts. He then

designed a symbol for Jeet Kune Do that consisted

of the Tai Chi symbol with two arrows around it

moving in opposite directions. This implied the

constant interchange between yin and yang. Within

a few years he was the top martial artist in the

world, attracting as students top fighters such

as Chuck Norris and Joe Lewis; and such celebrity

students as Steve McQueen, James Coburn, Blake

Edwards and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Bruce was trying to instill

in his students the natural spontaneity of

combat, to reach a point where the action becomes

thoughtless, where there is no separation between

the fighter and the fight. Lee believed that all

knowledge led to self-knowledge, and that he

could not teach his students so much as point

them in the direction of knowledge. "I

cannot teach you, " Bruce mused to James

Franciscus in the television series Longstreet,

"only help you to explore yourself."

Bruce did not believe in

learning by accumulation, but instead believed

that the highest form of mastery was one of

simplicity, of "stripping away the

inessentials", much like Lao Tzu believed in

the need to disband all schools of formal

learning. Indeed, Bruce disbanded his own school

system shortly before his death, lest his way be

taken as "the Way".

Soon after Lee got his own

break in Hollywood as Kato on the Green

Hornet series. It earned him

great popularity but folded after only one

season.

An offer by Raymond Chow's

Golden Harvest Studio in Hong Kong brought Lee

back to Asia to make the movie the Big

Boss. When the movie came

out, Lee became an overnight sensation throughout

Asia. Two more films followed: Fists

of Fury and

Way of the Dragon. In the

movie Way of the Dragon,

Lee demonstrates the Taoist principle of

adaptability in his climactic fight scene with

Chuck Norris. Having fought to a virtual

standstill, Lee begins to adapt his fighting

method from one of rigidity to one of pliancy,

and emerges the victor.

His fourth picture was

intended to further expound upon the theory of

flexibility as a means of survival. Entitled Game

of Death, the movie, as

conceived by Bruce Lee, would have begun like

this: "As the film opens we see a wide

expanse of snow. Then the camera closes in on a

clump of trees while the sounds of a strong gale

fill the screen. There is a huge tree in the

center of the screen, and it is all covered with

thick snow. Suddenly there is a loud snap, and a

huge branch of the tree falls to the ground. It

cannot yield to the force of the snow so it

breaks. Then the camera moves to a willow tree

which bending with the wind. Because it adapts to

the environment, the willow survives. What I want

to say is that a man has to be flexible and

adaptable, other wise he will be destroyed."

Though the movie was begun, Lee never finished

it, and the Game of Death that

reached theaters bore little resemblance to Lee's

original vision.

In 1972 Warner Brothers

approached Lee to make a movie for American

audiences. In the movie, Enter

the Dragon, Lee tried to

express some of his philosophy. In an early scene

in the film he discusses a sparring match with an

old Taoist priest. When the priest asks Lee what

he thought of his opponent when he was facing

him, Lee replies, "There is no opponent.

Because the word 'I' does not exist." The

priest is very pleased by his answer. This scene

was cut out of the American version because the

producers thought American audiences would be

turned off by all the philosophy mumbo jumbo.

Through it all he was still

teacher and guide to his friends. At the time he

was filming Enter the Dragon,

Bruce's friend Taky Kimura called him from the

United States with a personal crisis: Kimura's

marriage was falling apart and he was despondent

and suicidal. "I lost two brothers a month

apart and then my wife left me," said

Kimura.

Bruce told him, "Taky,

I haven't met your wife but I've counseled you

before. You must do everything in your power to

solve the thing but, at some point in time, you

may just have to walk on." Bruce was saying

that if nature dictated that the marriage was

over, going against it would only bring further

unhappiness. Bruce was expressing the Taoist

philosophy of wu-wei,

or following the course of nature without

resisting it. "Walk on," he would tell

Kimura, "walk on."

"Life is an

ever-flowing process and somewhere on the path

some unpleasant things will pop up-it might leave

a scar-but then life is flowing on, and like

running water, when it stops, it grows stale. Go

bravely on, my friend, because each experience

teaches us a lesson."

On July 20, 1973, Bruce Lee

died of a cerebral edema, three weeks before the

opening of Enter the Dragon,

three weeks before he would gain worldwide fame.

Lee was buried at Lakeview

Cemetery in Seattle, Washington. The casket was

covered in white, red, and yellow flowers making

up the yin/yang symbol. The pallbearers were

Steve McQueen, James Coburn, Bruce's brother

Robert, and Bruce's top student, Dan Inosanto. At

the graveside James Coburn had the last words:

Farewell, brother. It has been an honor to share

this space with you. As a friend and a teacher,

you have given to me, have brought my physical,

spiritual, and psychological selves together.

Thank you. May peace be with you."

On his tombstone was

engraved the message: "Your inspiration

continues to guide us toward our personal

liberation." His gravesite has been

faithfully cared for by his friend and student

Taky Kimura for the past twenty-five years.

|